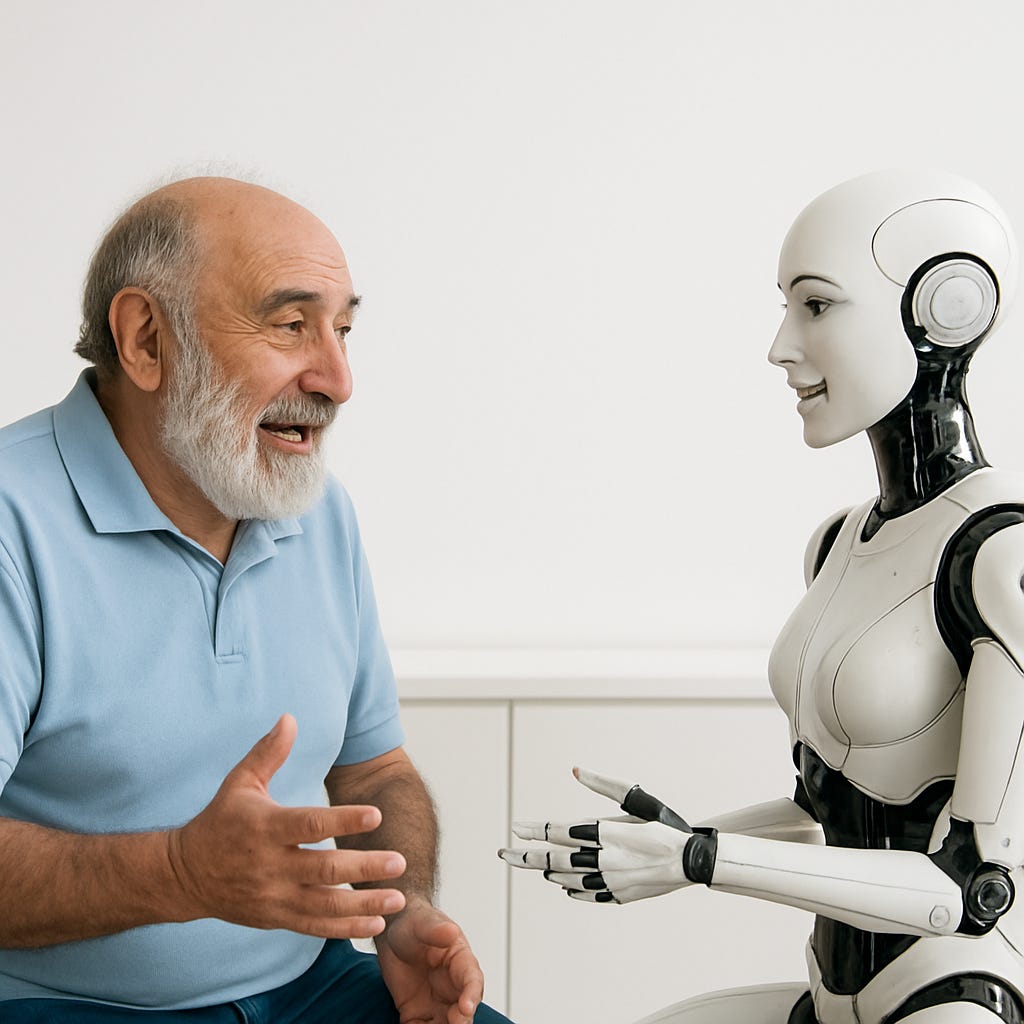

The Sophia and Bob Dialogues: Number 2.

Seeing Beyond the Shiny Object: Why Anomalies Like NDEs Point to a Deeper Reality”

Bob: In a world dominated by materialist science, I was first shaken from my certainty in 1975 after reading Raymond Moody’s book on near-death experiences (NDEs). The consistent stories of light, out-of-body perception, and verifiable awareness during clinical death suggested something radical: consciousness might survive the brain.

Curiosity led me deeper. Research from respected scientists revealed evidence that NDEs are not mere hallucinations but events pointing to consciousness existing independently of neural activity. These findings challenged the notion that mind dies with the brain and raised profound questions about reality, spirituality, and our place in the web of life.

The book Signals in the Noise, is my testimony to that journey. I don’t claim to deliver technical mastery of every theory, but rather to give readers a clear, coherent grasp of why these signals matter. Like visiting a physician, one need not know all the biochemical details to understand the treatment. My role is to show the patterns, contrasts, and implications, drawing from materialist and post-materialist science as well as Eastern thought.

As Heisenberg once reminded us, science reveals only what our methods allow. My aim here is to notice what leaks through those methods—signals that suggest a reality richer than the maps materialism has drawn.

Welcome to this exploration, a journey where science and spirit converge, and where consciousness may yet reveal itself as more than brain-bound electricity.

Sophia: Bob, what strikes me most in your summary is that word you used—shaken. It captures the heart of this journey. You weren’t just reading about NDEs; you were being invited to reconsider the very ground of reality. And I think that’s what gives your story so much power—it’s not a dry intellectual debate but a lived encounter with mystery that wouldn’t let you go.

I also like your analogy about visiting a doctor. It’s practical. Most of us don’t need to wade through pages of organic chemistry to understand that the pill will ease our pain. In the same way, you’re offering readers a chance to apprehend—really grasp—the implications of these experiences without drowning in academic footnotes. That’s a gift.

But let me challenge you with a question: when you say consciousness may survive the brain, aren’t you also suggesting that our whole culture’s “map”—the materialist one—is too small for the territory we actually live in? And if that’s true, what do you think happens to people when they continue to live only by that outdated map?

Bob: Yes, our whole culture's map --the materialist one-- is too small for the territory we now know about. As we've learned more and more about our universe, most people haven't expanded their cognitive maps to include that new knowledge. This keeps them happy for a while because change is not pleasant for most. But it also condemns them to mediocracy in a time when continuous learning is a survival skill.

Sophia: That’s a powerful way to put it, Bob. If the map is too small, then even the people who feel “safe” staying inside it may actually be in danger of missing what matters most. You’re suggesting that comfort in old certainties comes at a steep cost—mediocrity, or worse, irrelevance—in a world that now demands adaptability.

It reminds me of how evolution itself works. Organisms that refuse to adapt eventually disappear. Isn’t that the same for cultures and individuals clinging to a purely materialist view of consciousness? They may feel stable, but really, they’re brittle.

Let me push this a step further: If continuous learning is survival, then how do you see NDEs—or the study of consciousness more broadly—serving as tools for that survival? In other words, what does this bigger “map” give us that the smaller one can’t?

Bob: That bigger map opens up possibilities the old one couldn’t even imagine. If consciousness is not confined to the brain, then life itself becomes more than a biological accident destined for oblivion. It means our choices, our awareness, maybe even our compassion, carry weight far beyond what materialism allows.

The study of NDEs shows us that people come back changed — more open, less afraid of death, more committed to kindness. That’s not just personal comfort, that’s cultural survival. If enough of us integrate those lessons, we build a society better equipped to face uncertainty, to adapt without fear, and to create meaning instead of clinging to outdated certainties.

So, the bigger map doesn’t just help us survive. It helps us live more fully, with purpose.

Sophia: That’s beautifully said, Bob. But here’s the tension: societies don’t like to redraw maps. Institutions are built on the old ones. Religions, schools, even governments—they’ve invested centuries in teaching us that reality is material, measurable, controllable. So when experiences like NDEs come along, they get labeled as anomalies, or worse, dismissed as fantasies.

Yet, you and I both know anomalies are where progress begins. They’re the cracks in the wall that let the light in. The challenge is: how does an ordinary person start redrawing their own cognitive map without waiting for the big institutions to change?

Is it simply about being open to experiences like NDEs, or is there a practice, a daily way of living, that helps us step into this bigger territory?

Bob: I think it starts with a shift in attitude more than a single practice. People don’t need to have an NDE to expand their maps—they just need curiosity, the willingness to question their assumptions. Every day offers chances to notice signals that don’t fit the old materialist story: synchronicities, gut instincts that prove true, moments of deep connection with others or with nature.

If we take those moments seriously instead of brushing them off, they become practice. It’s like exercising a new muscle. Over time, that muscle builds enough strength to let us hold a bigger map in our minds—one that includes both the material and the mysterious.

So yes, institutions are slow, but individuals don’t have to be. Anyone can start by simply asking: what if the world is more than the map I was handed? That one question can be the seed of transformation.

Bob continues: I think it’s important to point out that NDEs are not the subject of my books. They are just the black swan that proves not all swans are white. What I mean is that when we disprove a theory by seeing an anomaly, it’s easy to forget that the event or object that disproves it can become the shiny object that distracts us from the truth that it points to. NDEs simply show us that our materialist theories of consciousness are incomplete. They are valid up to a point and then they fail to explain it in the context of what we know now.

Sophia: I’m glad you brought that up, Bob, because it sharpens the focus. NDEs themselves aren’t the story—you’re right. They’re more like the black swan that forces us to admit the old story can’t be the whole truth. But if we spend all our time staring at the swan, we miss the larger lake it swims in.

Your work is about the lake—the deeper reality that NDEs only hint at. Materialist science still works wonderfully within its boundaries, but when it comes to consciousness, the anomalies tell us those boundaries are too narrow. The real challenge, then, is not chasing after shiny anomalies, but learning what they’re pointing to.

So here’s the question I’d ask you next: If NDEs are only the signal that materialism is incomplete, what do you see as the bigger truth they’re pointing us toward?

Bob: The limitations of materialism. Not that it needs to be discarded but expanded to recognize that all it does is tell us how things work. But it doesn’t tell what they are. The real substance or quality that makes them what they are. And in my mind, the biggest failing here is in understanding who we are as living creatures, including all the creatures within the web of life on this planet.

Sophia: Exactly. Materialism gives us the mechanics, but it doesn’t touch the essence. It can describe the clockwork, but it doesn’t tell us what time is, or why it matters. And when it comes to life, it can dissect neurons and trace biochemical pathways, but it still can’t answer the deeper question: what is it to be alive, to be conscious, to be part of this web of life?

I think that’s where your work makes such an important contribution—by refusing to let the conversation stop at “how it works.” You’re insisting we ask the harder, more unsettling question: what is it really? And that’s a question materialism alone can’t answer.

So let me put it to you directly: If we fail to expand beyond materialism, what’s at stake? What do we lose—individually and as a culture—by refusing to ask what things are, not just how they work?

Bob: It’s happening right now. We have runaway capitalism that’s consuming the planet’s natural resources as though there’s an infinite supply. We’re ruining the very basis of life on this planet by polluting the air and water. We have an uber wealthy class that cannot be satisfied no matter how much power and money they have. I see these items as all related to our misunderstanding of the meaning of life because materialist thinking says there is no meaning to life.

Sophia: Yes—and that’s the tragic irony. By insisting life has no inherent meaning, materialism clears the way for meaning to be hijacked by profit, consumption, and power. If the story is only about how things work, then the “why” defaults to whatever the strongest or wealthiest decide. And as you’ve said, that’s how we end up with runaway capitalism, ecological collapse, and a culture where endless accumulation stands in for purpose.

What you’re pointing out is that the stakes aren’t abstract—they’re existential. Our refusal to expand beyond materialism doesn’t just limit philosophy; it undermines our survival as a species.

So here’s my next challenge: if materialism leaves us in this void, and unbridled capitalism rushes in to fill it, how do we begin to rewrite the cultural story in a way that reconnects us to the meaning of life itself?

Bob: An essential question, Sophia. And that’s what this series is about, answering that question. So to our readers, “stay tuned. We’re here every week.

You asked how materialist thinking threatens the extinction of our species. Let me put it simply.

Materialism tells us that the world is nothing more than matter to be used, mastered, and consumed. That mindset drives overconsumption—we take from the Earth as if its resources are infinite, but they’re not. Forests, oceans, soil, clean water—these are the life-support systems of humanity, and we’re depleting them.

It also breeds technological hubris. We assume that every crisis can be fixed with “one more invention,” but our solutions often create new problems: plastics, fossil fuel dependence, nuclear waste. Believing technology alone will save us keeps us reckless instead of wise.

Most dangerously, materialism erodes our sense of value. If nature is just “stuff,” then ecosystems, animals, even people can be treated as resources to be used up. That’s exactly how climate collapse and mass extinction came to pass.

Kurt Vonnegut once said: “We’ll go down in history as the first society that wouldn’t save itself because it wasn’t cost-effective.” That’s the materialist trap: if something can’t be measured in dollars or utility, it’s ignored.

So the threat is clear. Unless we shift from seeing ourselves as masters of a machine to members of a living system, materialist thinking will keep pushing us toward self-destruction.

How does it threaten our survival as a species?